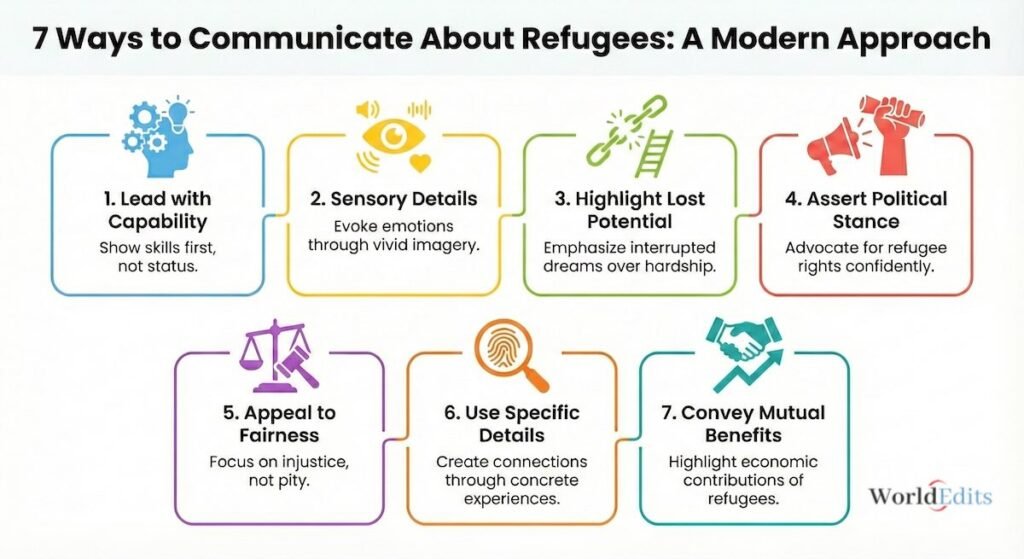

📌 Three Takeaways:

- Lead with the person’s profession and skills before mentioning displacement to establish them as capable individuals.

- Use specific sensory details and parallel experiences to help readers see themselves in refugee stories.

- Frame support as addressing injustice and unlocking potential, not rescuing helpless victims.

Writing about refugees without sounding preachy requires leading with capability rather than victimhood, using specific details instead of generic suffering, and framing support as addressing injustice rather than rescuing the helpless.

Most NGO content fails because it opens with refugee status instead of the person, relies on pity instead of fairness, and uses abstract descriptions instead of concrete details. This article shows you how to fix each of these problems with practical techniques you can apply immediately.

Contents

Start from zero: Define what a refugee actually is

Most readers don’t actually know the legal definition of a refugee, and that confusion creates distance. Start by clarifying what you mean because precision builds credibility.

The 1951 Refugee Convention defines a refugee as someone who has fled their country due to “a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion.” This isn’t someone who chose to leave for better opportunities. This is someone who had to leave or face persecution, violence, or death.

Don’t assume your readers understand this distinction. Spell it out early in your content, particularly when addressing audiences who might conflate refugees with other migrant groups. Use plain language: “A refugee didn’t choose to leave home. They had to flee to survive.”

NaTakallam, which connects refugees with language learners for online tutoring, handles this definition brilliantly. They clarify that their tutors are “displaced persons” but immediately pivot to credentials. A typical profile reads: “Mona is a Fine Arts graduate from Damascus University. She is now an Arabic tutor specializing in conversational practice and cultural context.” The displacement is acknowledged in one phrase, then the focus shifts entirely to professional qualifications.

Their imagery reinforces this approach – tutors appear in professional settings with headsets and teaching materials, looking directly at the camera as peers to their students. There’s no “exotic” or “suffering” gaze, just professionals offering a service.

Once you’ve established this baseline, you can build on it. Explain the asylum process briefly if it’s relevant to your story. Mention that refugees often wait years in camps or temporary housing before resettlement. Give context about the barriers they face: language requirements, credential recognition, work permits.

This foundation prevents readers from making assumptions. It also preempts the “why don’t they just go home?” question by making it clear that home isn’t safe.

Draw parallels between their lives and your readers’ lives

The most effective refugee stories highlight similarities before differences. Start with the ordinary, relatable aspects of someone’s life before displacement.

Write: “Fatima ran a bakery in Damascus. She woke at 4 a.m. to prep dough, managed three employees, and worried about her daughter’s math grades.” Don’t write: “Fatima is a refugee who fled Syria.”

The first version establishes her as someone your readers can relate to: a small business owner, an early riser, a parent concerned about education. The second version leads with her status as a refugee, which immediately creates distance.

IKEA’s Skills for Employment stories demonstrate this technique perfectly. Their refugee employee profiles don’t start with war or camps – they start with the work day. They describe team dynamics, customer service interactions, and the specific tasks someone handles on the floor. One story might open with someone describing their morning routine, their role training new hires, or their goals for advancement within the company. This creates immediate identification for any reader who has held a job, managed colleagues, or worked toward a promotion.

The quotes IKEA features focus on confidence and future ambitions: “I want to build a life on my terms” or “I’m proud of what I contribute to my team.” These statements could come from anyone in your readers’ professional network, which is exactly the point.

Use details that mirror your readers’ lives. If you’re writing for corporate audiences, mention refugees who were accountants, project managers, or HR directors. If you’re writing for parents, lead with parenting concerns. If you’re writing for small business owners, start with entrepreneurship.

This technique works because it activates the reader’s sense of “that could be me.” When they see themselves in the refugee’s pre-displacement life, the loss becomes personal. They understand what it would mean to lose their business, their home, their routine, their sense of normalcy.

Avoid exotic or othering details in the opening. Don’t lead with unfamiliar foods, clothing, or customs. Save cultural specifics for later, after you’ve established common ground. Your goal in the opening is identification, not fascination.

Highlight lost potential, not just current suffering

Readers respond more strongly to loss and injustice than to abstract suffering. Frame your stories around what was taken, what could have been, and what still could be.

Instead of: “Ali lives in a refugee camp with limited access to healthcare.”

Write: “Ali was two semesters away from finishing his engineering degree when the war started. He’d already accepted a job offer at a construction firm in Aleppo. Now he fixes phones in a camp in Jordan, using the same problem-solving skills he’d planned to apply to bridge design.”

The second version shows capability, ambition, and interrupted potential. It creates a sense of waste and injustice that motivates readers more effectively than descriptions of hardship alone.

Talent Beyond Boundaries is really good at this approach. Rather than leading with displacement, they frame the entire conversation around labor market solutions. Their messaging focuses on “refugee skill underutilization” as a waste of human capital, immediately activating readers’ sense of unfairness and inefficiency. Headlines like “Refugees are doctors, engineers, and skilled trade workers” establish professional identity first, displacement second.

This framing also makes the call to action more compelling. You’re not asking readers to “help someone in need.” You’re asking them to “help unlock potential that’s being wasted” or “help someone get back to the career they earned.”

Quantify the loss when possible. “She spent seven years training as a surgeon” hits harder than “she’s a doctor.” “He built a business that employed 15 people” conveys more than “he owned a company.”

But don’t dwell on tragedy for its own sake. Always connect the loss to forward momentum. Show what the person is doing now to rebuild, what they’re working toward, and what barriers stand in their way. The emotional arc should move from capability, to loss, to resilience and action.

When (and how) to take a political stance

Many NGOs shy away from political statements, fearing they’ll alienate donors. This is often a mistake. Readers respect organizations that have clear values and aren’t afraid to state them.

If your organization believes that refugee policies are unjust, say so. If you think work permit restrictions are counterproductive, make the case. But do it with evidence, not rhetoric.

Strong version: “Current policies require refugees to wait 18 months before they can legally work. This forces qualified professionals into poverty and costs the economy an estimated $X billion in lost productivity annually. We believe refugees should have immediate work authorization.”

Weak version: “We think it would be nice if refugees could work sooner.”

The strong version takes a clear position and backs it with data. It appeals to both moral values (fairness) and practical concerns (economic loss). The weak version sounds tentative and fails to give readers a reason to care.

When taking political stances, focus on specific policies rather than broad ideologies. “We support reducing asylum processing times from 24 months to 6 months” is more actionable than “we support immigrants.” Specific positions give readers clear things to advocate for.

NaTakallam takes a political stance through market solutions rather than policy advocacy. They frame language tutoring as a “fair exchange of value for a high-quality service” rather than a donation, making the case that economic inclusion works better than aid dependency. This is inherently political – it challenges the assumption that refugees need charity rather than opportunities – but it’s delivered through a business model rather than a policy platform.

Don’t apologize for your values. Phrases like “we understand this is controversial, but…” or “we know not everyone will agree…” undermine your authority. State your position confidently, explain your reasoning, and trust your audience to engage with the argument.

That said, distinguish between organizational advocacy and partisan politics. You can advocate for policy changes without endorsing political parties. Frame your positions around outcomes and evidence rather than left/right talking points.

Appeal to fairness and injustice, not pity

Readers don’t want to feel sorry for people. They want to feel motivated to address unfairness. Frame your stories around violated norms and broken systems rather than victimhood.

Fairness framing: “Amina passed her medical licensing exam with a higher score than 60% of native applicants. But immigration rules won’t recognize her Syrian medical degree, so she cleans hospitals instead of treating patients in them. The same hospitals facing nursing shortages.”

Pity framing: “Amina struggles to make ends meet as a cleaner, even though she was a doctor in Syria.”

The first version creates anger at a broken system. It highlights absurdity and waste. The second version just makes readers feel bad, which is less motivating and easier to tune out.

Use words like “unfair,” “absurd,” “wasteful,” and “counterproductive.” These terms activate different emotional responses than “sad,” “difficult,” or “challenging.” They imply that something can and should be fixed rather than simply endured.

Point out specific injustices that violate common sense. “She’s not allowed to work, but she’s also not allowed to receive long-term aid. She’s expected to survive on nothing.” These contradictions make readers angry at the system rather than pitying the individual.

Research supports this approach. According to the Tent Partnership for Refugees and New York University’s Stern School of Business, 44% to 77% of consumers (depending on age and region) are more likely to buy from brands that support refugees. People want to align with fairness and justice, not charity.

Use specific sensory details that create presence

Generic descriptions fail. Specific details make readers feel like they’re there, which creates emotional connection without manipulation.

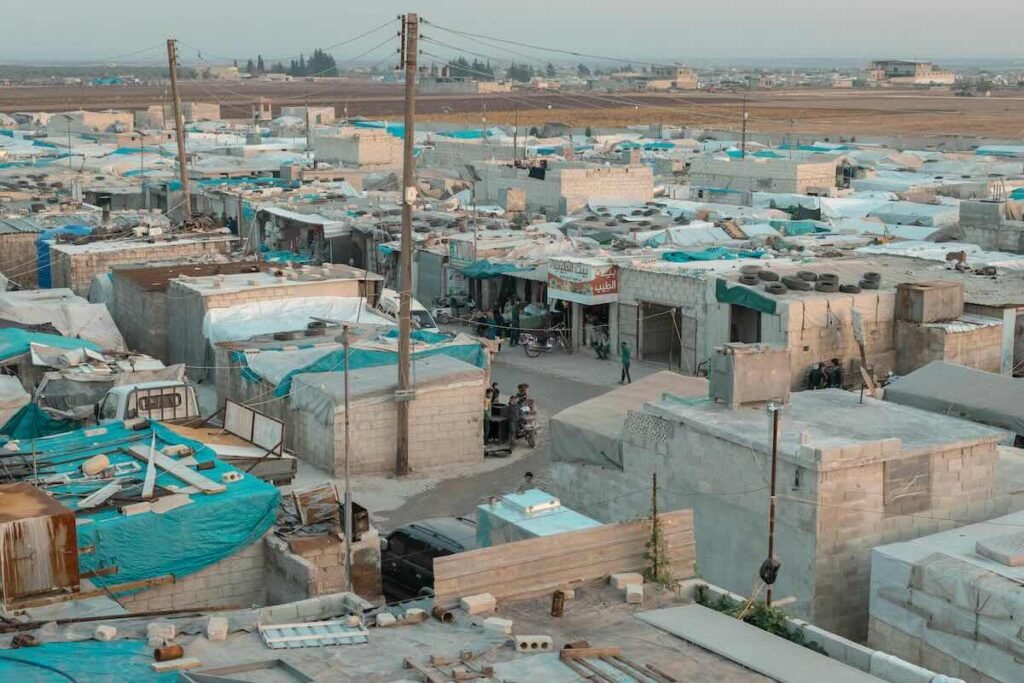

Generic: “The camp was crowded and difficult.”

Specific: “The tent walls are so thin she can hear her neighbor’s alarm clock at 5 a.m. Three families share one water tap. When it rains, the walkways between tents turn to mud that sticks to everything.”

The specific version doesn’t tell readers how to feel. It just shows them what daily life looks like and lets them draw their own conclusions. This feels more honest and therefore more persuasive.

Use all five senses. What does the person see when they wake up? What do they hear? What does the air smell like? What textures do they encounter? What do they taste?

But choose details strategically. You want details that illuminate experience, not details that exoticize or create spectacle. The point isn’t to make readers gawk at hardship. The point is to make abstract situations concrete.

Focus on details that show ingenuity and problem-solving rather than just deprivation. “She rigged a solar panel to charge phones for other families, which gives her enough income to buy vegetables twice a week” tells you about both conditions and capability.

Avoid clichés about suffering. Don’t describe “hopeless eyes” or “broken spirits.” These phrases are lazy and manipulative. Instead, show what the person actually does and says, and let readers form their own impressions.

Benefits for the reader: Beyond “feeling good about yourself”

Many NGOs end with vague appeals to compassion. “Support refugees because it’s the right thing to do.” This is weak. Give readers concrete reasons why refugee support benefits them and their communities directly.

Economic benefits are measurable. Research from the National Bureau of Economic Research shows that refugees pay $21,000 more in taxes over their first 20 years in the U.S. than they receive in benefits. Supporting refugee integration isn’t charity – it’s investing in people who will contribute to the tax base, fill labor shortages, and start businesses.

OECD research projects that working-age populations across member countries will decline by 8% by 2060, with more than a quarter of nations experiencing declines exceeding 30%. Refugee integration directly addresses this demographic crisis, providing skilled workers for healthcare, technology, and skilled trades where shortages are already acute.

Talent Beyond Boundaries builds their entire value proposition around this mismatch. They explicitly position refugees as the solution to labor shortages in the Global North, using language like “refugees solve your talent gap” rather than “refugees need your help.” This reframing turns support into self-interest, which is far more sustainable than appeals to charity.

For businesses, the case is even stronger. McKinsey & Company’s diversity research found that companies in the top quartile for ethnic diversity were 35% more likely to have financial returns above their industry median. We’ve written extensively about the business case for refugee support for corporate leaders evaluating these programs.

Employee retention represents another tangible benefit. Research from the Fiscal Policy Institute and Tent Partnership found that in manufacturing, refugee turnover rates hit approximately 4% compared to an 11% industry average. Lower turnover means reduced hiring costs, stronger institutional knowledge, and more stable teams.

IKEA’s corporate storytelling explicitly leverages this data point. Their Skills for Employment content doesn’t just share feel-good stories – it cites retention rates and innovation benefits directly. They frame refugee employment as solving business problems (labor shortages, high turnover) rather than fulfilling corporate social responsibility quotas. This positioning makes the case to CFOs and operations managers, not just HR departments.

For individual readers, frame support in terms of community strength. Refugee professionals fill gaps in local services. Refugee entrepreneurs open businesses that create jobs. Refugee families revitalize declining neighborhoods and support local schools.

The 2024 Edelman Trust Barometer found that business is the most trusted institution globally, which means corporate engagement with refugee issues carries significant credibility and influence. Supporting refugees aligns with broader consumer values, particularly among younger demographics who represent future market share.

Don’t ignore the moral dimension, but don’t make it the only argument. “This is right, and it also makes economic sense” is more persuasive than either argument alone. Give readers permission to feel good about supporting something that also serves their practical interests.

Putting it into practice

You can’t fix your refugee communications overnight, but you can start with one piece of content. Choose a recent blog post, fundraising email, or social media campaign. Review it against these questions:

- Do you define what a refugee is, or do you assume readers know?

- Do you lead with the person’s profession and capabilities, or with their refugee status?

- Do you draw parallels to your readers’ lives, or keep the story distant and foreign?

- Do you highlight lost potential and injustice, or just describe hardship?

- Do you take clear positions on policies, or stay vague and apologetic?

- Do you frame support as addressing unfairness, or as rescuing victims?

- Do you use specific sensory details, or generic descriptions?

- Do you give readers concrete benefits beyond “feeling good,” or rely solely on moral appeals?

Pick the one area where you’re weakest and rewrite that section. Then test the new version with a small audience and see what resonates. Iterate from there.

If you’re struggling to find the right tone or need expert guidance on culturally sensitive framing, specialized writing support can help you refine your approach. At WorldEdits, we work with NGOs to create content that drives action without manipulation, using techniques built from years of trial and refinement in the sector.

You’re not seeking perfection, just progress toward communication that treats refugees as capable people facing unjust barriers rather than helpless victims needing rescue.

That shift in framing makes all the difference in how readers respond and what actions they take. Hopefully, it’ll also help you take another step toward making the world a better place for people forced into injustice.